CASE PRESENTATION

Acute viral hepatitis type A with biphasic cholestatic behavior: Case presentation

Hepatitis viral aguda tipo A de comportamiento bifásico colestásico: Presentación de un caso

Yasmany Salazar Rodríguez 1*, https://orcid.org/0009-0002-0581-847X

Aliuska Cadet Cobas 2, https://orcid.org/0009-0004-5022-5846

Ibis Umpierrez García 1, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1850-4453

Thais de la Caridad Roca Alvarez 2, https://orcid.org/0009-0002-7670-0460

1 Dr. Mario Muñoz Monroy Military Hospital “Carlos Juan Finlay Order”. Matanzas, Cuba.

2 University of Medical Sciences of Matanzas. Matanzas, Cuba

* Corresponding author: yasmanyailen@gmail.com

Received: 22/01/2025

Accepted: 23/05/2025

How to cite this article: Salazar-Rodríguez Y, Cadet-Cobas A, Umpierrez-García I, Roca-Alvarez TdlC. Acute viral hepatitis type A with biphasic cholestatic behavior: Case presentation. MedEst. [Internet]. 2025 [cited access date]; 5:e319. Available in: https://revmedest.sld.cu/index.php/medest/article/view/319

ABSTRACT

Introduction: hepatitis A is an infectious-contagious disease of universal distribution. Where the presence of outbreaks in areas of overcrowding and poor sanitation is visualized. Although in general this disease has a favorable evolution, there are reports of complications and atypical forms of presentation such as the present case in question, which have an impact on the morbidity and mortality of patients.

Objective: to present a patient with biphasic, cholestatic behavior with Hepatitis A.

Case presentation: a 20-year-old white male patient, smoker, with the epidemiological history of having been diagnosed with hepatitis A 30 days earlier, during an outbreak in his living area, with a favorable evolution; but after the month of convalescence; It begins with marked ichterus, intense pruritus, choluria, acolia, abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium, and epixtasis. Physical examination revealed the presence of rubin ichterus, scratching lesions, and tenderness in the upper abdomen, with painful hepatomegaly of 3 cm. Therefore, he was admitted with a diagnosis of cholestatic biphasic hepatitis, the diagnosis was corroborated with the performance of pertinent complementary tests, he was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid where he had a favorable clinical evolution.

Conclusions: this study allowed us to observe the small number of cases reported with atypical presentation of Hepatitis A disease and the importance of a timely diagnosis from primary health care to prevent fatal complications of hepatitis.

Keywords: Biphasic Hepatitis A; Cholestatic Hepatitis; Fulminant Hepatitis; Acute Viral Hepatitis

RESUMEN

Introducción: la hepatitis A es una enfermedad infecto-contagiosa de distribución universal. Donde se visualizan la presencia de brotes en áreas de hacinamiento y saneamiento deficiente. Aunque de manera general esta enfermedad cursa con una evolución favorable, existen reportes de complicaciones y formas de presentarse atípicas como el presente caso en cuestión, que repercuten en la morbimortalidad de los pacientes.

Objetivo: presentar un paciente con Hepatitis A de comportamiento bifásico, colestásico.

Presentación de caso: paciente masculino blanco de 20 años de edad, fumador, con el antecedente epidemiológico de haber sido diagnosticado de hepatitis A 30 días antes, durante un brote en su área de convivencia, con una evolución favorable; pero pasado el mes de convalecencia; comienza con íctero marcado, prurito intenso, coluria, acolia, dolor abdominal en hipocondrio derecho y epixtasis. Al examen físico se describe a la inspección la presencia íctero rubínico, lesiones por rascado, y de dolor a la palpación en hemiabdomen superior, con hepatomegalia dolorosa de 3 cm. Por lo que se ingresa con diagnóstico de Hepatitis de comportamiento bifásico colestásico, se corroboró el diagnóstico con la realización de complementarios pertinentes, llevó tratamiento con ácido ursodexsicólico donde tuvo una evolución clínica favorable.

Conclusiones: este estudio permitió observar el poco número de casos reportados con presentación atípica de la enfermedad de la Hepatitis A y la importancia de un diagnóstico oportuno desde la atención primaria de salud para prevenir complicaciones mortales de la hepatitis.

Palabras Claves: Hepatitis A Bifásica; Hepatitis Colestásica; Hepatitis Fulminante; Hepatitis Viral Aguda

INTRODUCTION

Infectious diseases are one of the most frequent causes of morbidity and mortality in children and young adults, particularly in the developing world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the hepatitis epidemic is one of the leading health problems worldwide, both due to the millions of people affected and the number of patients who develop complications and chronic liver disease. (1) Among these, acute viral hepatitis type A (AVH) has increased its incidence. It is estimated that 1.5 million people are infected each year with this virus, primarily hepatotropic. (2)

Hepatitis A is an acute liver infection caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV). It is a benign, self-limiting disease that is not chronic. Suffering from it confers lifelong immunity and can be prevented through vaccination. HAV is transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route, with risk factors including ingestion of contaminated food and/or water and direct physical contact, among others. (3,4) Clinical manifestations range from asymptomatic patients to fulminant hepatitis.(5)

Icteric hepatitis is the classic presentation of the disease, characterized by nonspecific clinical manifestations compatible with acute viral infection. However, as evidenced in this report, atypical forms can develop, including: (5)

1. Biphasic variant: With recurrence of symptoms after initial improvement

2. Cholestatic form: Marked by persistent jaundice (bilirubin >5 mg/dL), intense pruritus, and disproportionate elevation of alkaline phosphatase

These atypical presentations represent only 7–15 % of cases according to recent series (5,7). Extrahepatic complications, although rare (<1 %), include pancreatic involvement (acute pancreatitis), renal involvement (glomerulonephritis), cardiovascular manifestations (pericarditis), and neurological complications (encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome). This case particularly illustrates the importance of recognizing these atypical patterns to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary therapy. (6)

Atypical forms include recurrent hepatitis, prolonged or persistent cholestasis, fulminant liver failure, or liver failure associated with autoimmune hepatitis. The typical clinical course of acute hepatitis A virus infection is spontaneously remitting in more than 90 % of cases; however, atypical courses have a prevalence that varies from <1 % to 20 % depending on the manifestation (overall, ∼7%). (6,7)

There is little information on the atypical clinical courses of hepatitis A virus infection, and it is important to mention that the lack of recognition of these often leads to the performance of multiple studies and treatments in clinical practice, which are not only unnecessary but also harmful.(7) Therefore, the authors of this study aimed to present a case of biphasic cholestatic hepatitis A admitted to the Dr. Mario Muñoz Monroy Military Hospital "Carlos Juan Finlay Order."

CASE PRESENTATION

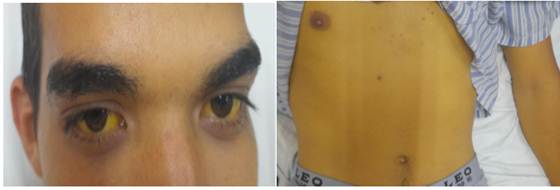

A 20-year-old Caucasian male, resident in an urban area, a smoker, with no relevant medical history, was admitted to the Military Hospital of Matanzas with marked jaundice after having presented with acute viral hepatitis type A (AVH) two months earlier during an outbreak in his community. He also reported intense pruritus, pain in the right upper quadrant and epigastrium, asthenia, anorexia, dark urine, acholia, and mild epistaxis on two occasions. Physical examination revealed jaundice initially ruby-colored (Figure 1), which evolved to greenish hues, along with scratch excoriations. Abdominal palpation revealed pain in the upper abdomen and a 3 cm hepatomegaly.

Figure 1. Yellow-green skin coloration (cholestatic jaundice) is observed in the patient upon admission.

The following (most significant) supplements are performed:

|

Complementary |

I |

II* |

III |

IV |

|

TGO (U/L) |

1024 |

820 |

222 |

49 |

|

TGP (U/L) |

1059 |

858 |

334 |

71 |

|

FA (U/L) |

319 |

461 |

402 |

241 |

|

GGT (U/L) |

- |

29 |

23 |

26 |

|

LDH (U/L) |

- |

418 |

250 |

178 |

|

PT (g/L) |

- |

83 |

76,4 |

77 |

|

Albumin (g/L) |

- |

44 |

38,2 |

44.7 |

|

Blood glucose (mmol/L |

3,4 |

3,24 |

4,09 |

4,4 |

|

Cholesterol (mmol/L) |

2,9 |

3,26 |

3,78 |

5,55 |

|

TG (mmol/L) |

2,48 |

2,82 |

2,86 |

1,71 |

|

Creatinine (mmol/L) |

- |

39 |

62 |

94 |

|

Urea (nmol/L) |

- |

4,79 |

5,75 |

6,2 |

|

Ac. Uric (mmol/L) |

311 |

318 |

334 |

351 |

|

Amylase (U/L) |

56 |

86 |

78 |

98 |

|

Total Bil. (g) |

206,7 |

- |

- |

175 |

|

Bil. Direct (g) |

- |

- |

- |

155 |

|

HTO (g/L) |

0,44 |

- |

- |

0,40 |

|

ESR (mm/H) |

23 |

- |

- |

10 |

|

Cuagulogram |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

TP-C (sec) |

13 |

- |

- |

- |

|

TP-P (sec) |

11,5 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cerules plasmin (g/L) |

- |

- |

0,34 |

- |

Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol) was initiated. Serological studies were negative, except for an elevated IgA level (2,18 g/L; normal value: X-Y), with IgG and IgM within normal ranges.

An abdominal ultrasound showed a 2,5 cm hepatomegaly (homogeneous parenchyma), a gallbladder with 8 mm wall thickening (double contour) and septation, as well as mild splenomegaly (1 cm). No free fluid or lymphadenopathy was observed in the abdominal cavity. The lung bases and electrocardiogram were normal.

With these findings, the diagnosis of acute viral hepatitis type A (AVH) with atypical presentation was confirmed. The patient received treatment with ursodiol (15 mg/kg/day) and showed favorable clinical progress. He was discharged with outpatient follow-up.

DISCUSSION

According to the literature, more than 90 % of cases of acute viral hepatitis type A (AVH) follow a self-limited course, with spontaneous resolution in 4–8 weeks. However, up to 20 % may present atypical courses, including biphasic, cholestatic, or fulminant forms. (2,6) Muñoz SG et al.,(5) in a series of Mexican cases during HAV outbreaks, highlight the limited information available on these atypical presentations, particularly regarding their pathophysiology (possibly related to an exacerbated immune response or host genetic factors).

This report is relevant by documenting a case of biphasic cholestatic hepatitis A, contributing to the limited evidence on these atypical variants. Our findings are consistent with those reported by Muñoz SG et al. (5) regarding the recurrence of symptoms after apparent improvement, but differ in the marked cholestatic component (greenish jaundice, intense pruritus) observed in our patient. This presentation reinforces the need to consider atypical forms in the differential diagnosis of acute cholestasis, especially in endemic areas.

The biphasic presentation with exacerbation of symptoms (progressive jaundice, intense pruritus, and painful hepatomegaly) and marked elevation of liver enzymes (SGOT 1024 U/L, SGPT 1059 U/L) required a thorough differential diagnosis. The following etiologies were prioritized: (8,9)

1- Autoimmune diseases: Autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibodies, anti-LKM1 negative; IgG normal)

2- Other viral hepatitis:

• Acute: hepatitis E (serology negative), CMV/EBV (IgM negative)

• Chronic: hepatitis B (HBsAg negative) and C (anti-HCV negative).

3- Systemic infections: HIV (ELISA negative), syphilis (VDRL negative).

4- Obstructive cholestasis: Ruled out by ultrasound (no biliary tract dilation).

The absence of positive markers for these alternatives, together with the epidemiological history of an HAV outbreak, reinforced the diagnosis of atypical hepatitis A. (8,9)

As noted by Báez-Sarria et al. (6) in their report of an atypical case of hepatitis A, it is essential to consider this diagnostic possibility to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures. In line with this approach, in the present case, the clinical method and noninvasive complementary studies (serology, ultrasound, and biochemical profiles) were prioritized, reserving liver biopsy only for cases without a conclusive diagnosis after this initial evaluation. It should be noted that the study faced logistical limitations, particularly the shortage of some reagents, which required interinstitutional coordination to complete the necessary analyses.

The treatments reported in published articles were reviewed, and they include expectant management (10) and the use of (Ursodiol®) for cases of recurrent and cholestatic hepatitis; the use of acetylcysteine for fulminant hepatitis; and corticosteroids for those with an autoimmune component. It should be noted that the use of steroids can trigger recurrent hepatitis. (2,7)

This was discussed within the medical community, and it was decided to begin treatment with Ursodiol® after analyzing the national and international evidence presented. The patient presented a favorable clinical outcome.

A literature review revealed various therapeutic alternatives depending on the clinical presentation: expectant management for mild cases (10), ursodeoxycholic acid (Ursodiol®) for recurrent or cholestatic forms, acetylcysteine for fulminant hepatitis, and corticosteroids when there is an autoimmune component, although with the potential risk of triggering recurrences. (2,7)

After a multidisciplinary analysis that considered both international evidence and national guidelines, it was decided to initiate treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (15 mg/kg/day), given the marked cholestatic component of the case. This therapeutic decision was associated with a progressive clinical and biochemical improvement (bilirubin reduction from 206,7 to 175 μmol/L in one week), validating the selected approach.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlighted the small number of reported cases with atypical presentations of hepatitis A and the importance of timely diagnosis in primary health care to prevent life-threatening complications of hepatitis.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Rojas Peláez Y, Trujillo Pérez YL, Reyes Escobar AD, Bembibre Mozo D. Some considerations on the chronic viral hepatitis as a health problem. MEDISAN [Internet]. 2021 [cited 22/01/2025]; 25(4): 965-981. Available in: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1029-30192021000400965&lng=es

2. Mehta P, Reddivari AKR. Hepatitis. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; [Internet]. 2023 [cited 22/01/2025]. Available in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554549/

3. Herrera JA, Badilla J. Hepatitis A. Med. leg. Costa Rica [Internet]. 2019 [cited 22/01/2025]; 36(2):101-7. Available in: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1409-00152019000200101&lng=en&tlng=es

4. Jeong S, Lee H-S. Hepatitis A: Clinical manifestations and management. Intervirology [Internet]. 2010 [cited 22/01/2025]; 53(1):15-9. Available in: http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000252779

5. Muñoz SG, Díaz HA, Suárez D, Sánchez JF, Gamboa A, García I, et al. Manifestaciones atípicas de la infección por el virus de la hepatitis A. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2018 [cited 22/01/2025]; 83(2):134-43. Available in: http://www.revistagastroenterologiamexico.org/es-manifestaciones-atipicas-infeccion-por-el-articulo-S0375090618300636

6. Báez Sarria F, Martinez Romero M, Ferrer Santos V, Peña Alvarez D. Hepatitis viral aguda tipo A colestásica con manifestaciones extrahepáticas y complicaciones neurológicas poco frecuentes. Rev Cubana Med Milit [Internet]. 2024 [cited 22/01/2025];53(2). Available in: https://revmedmilitar.sld.cu/index.php/mil/article/view/21781/2506

7. Herrera Corrales JA, Badilla García J. Hepatitis A. Med. leg. Costa Rica [Internet]. 2019 [cited 22/01/2025]; 36(2): 101-107. Available in: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1409-00152019000200101&lng=en

8. Castellanos-FernándezI M, Teixeira-Brado E, La-Rosa-Hernández D, Dorta-Guridi Z, Rodriguez-Pelier C, Vega-Sánchez H. Infección crónica por virus de hepatitis B. Instituto de Gastroenterología de Cuba, 2016-2018. Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas [Internet]. 2019 [cited 22/01/2025]; 19 (1):[aprox. 14 p.]. Available in: https://revhabanera.sld.cu/index.php/rhab/article/view/2669

9. Akpor Oluwaseyi A, Adelusi Folusho A, Akpor Oghenerobor B. Conocimiento, nivel de riesgo y prevalencia de la hepatitis B y C entre los conductores de minibuses comerciales en Ado-Ekiti, estado de Ekiti, Nigeria. Enferm. glob. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 22/01/2025]; 22(71): 371-406. Available in: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412023000300012&lng=es

10. Velasco Martínez FI, Sandoval Suárez LJ, Ehrhardt Morón EM, Mora Bautista VM. Hepatitis colestásica persistente por virus de hepatitis A en pediatría. Reporte de Caso. Pediatria. [Internet]. 2023 [cited 22/01/2025]; 55(Suplemento 1):7-10. Available in: https://revistapediatria.org/rp/article/view/189

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

YSR: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Research, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing, Writing - Review and Editing.

ACC: Conceptualization, Research, Resources, Visualization, Writing - Review and Editing.

IUG: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Research, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - Review and Editing.

TdlCRA: Conceptualization, Research, Resources, Visualization, Writing - Review and Editing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

The authors did not receive any funding for the development of this article.