SYSTEMATIC REVIEW ARTICLE

Cell therapy in regenerative medicine: a systematic review of clinical applications

Terapia celular en medicina regenerativa: revisión sistemática de aplicaciones clínicas

Duany Delgado Bermúdez 1*, https://orcid.org/0009-0006-2605-1692

Dayana Bermúdez Sañudo 2, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7474-9642

Maylin Gutiérrez Martínez 1, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7043-7684

Lissel de la Caridad Ramírez Gómez 1, https://orcid.org/0009-0002-8719-9755

Lorena González Berrio 1, https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0092-4818

1 University of Medical Sciences of Matanzas. Faculty of Medical Sciences of Matanzas “Dr. Juan Guiteras Gener”, Matanzas. Cuba.

2 Provincial Gynecological and Obstetrical Hospital “José Ramón López Tabrane”. Matanzas, Cuba.

* Corresponding author: duanydelgadobermudez@gmail.com

Received: 10/10/2025

Accepted: 01/02/2026

How to cite this article: Delgado-Bermúdez D; Bermúdez-Sañudo D; Gutiérrez-Martínez M; Ramírez-Gómez LdlC; González-Berrio L. Cell therapy in regenerative medicine: a systematic review of clinical applications. MedEst. [Internet]. 2026 [cited access date]; 6:e500. Available in: https://revmedest.sld.cu/index.php/medest/article/view/500

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Regenerative medicine based on cell therapy has experienced rapid expansion in response to the increase in chronic degenerative diseases and dissatisfaction with conventional palliative treatments, although methodological challenges persist that hinder its clinical translation.

Objective: To synthesize the recent scientific evidence on the efficacy, safety, and clinical applications of stem cell therapy.

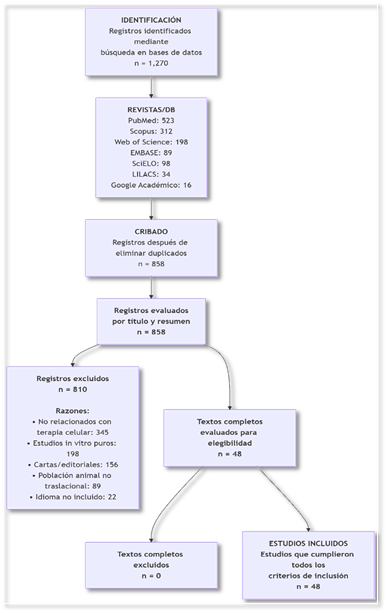

Methodology: PRISMA 2020 systematic review. Searches were conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, SciELO, LILACS, and Google Scholar (2019–2024). Forty-eight studies were included (clinical trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, and preclinical studies). Quality was assessed using Cochrane RoB 2, Newcastle-Ottawa, AMSTAR 2, and SYRCLE. A narrative synthesis was performed by specialty and cell type.

Results: Musculoskeletal (20.8%), neurological (14.6%), and dermatological (12.5%) applications predominated. Mesenchymal stem cells were the most frequently used (45.8%). In knee osteoarthritis, they showed a reduction in pain of 1.8 points (VAS) and an improvement of 12.3 points (WOMAC). In Parkinson's disease, they showed an improvement of 8.5 points (UPDRS-III) with 15% dyskinesias. Hematopoietic stem cells maintain established indications (5-year survival rate of 40-70%, graft-versus-host disease rate of 30-50%). Mesenchymal stem cells have a favorable safety profile, with the most common adverse effects being local pain (10-20%), mild fever (5-12%), and joint edema (5-8%).

Conclusions: Cell therapy shows moderate efficacy in osteoarthritis and Parkinson's disease, with excellent safety for mesenchymal stem cells. Hematological applications constitute a standard of care. The evidence is limited by methodological heterogeneity and short follow-up periods. Randomized phase III trials with long-term follow-up are required to solidify indications.

Keywords: Stem Cells; Regenerative Medicine; Cell Therapy; Systematic Review; Efficacy; Safety.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la medicina regenerativa basada en terapia celular ha experimentado expansión acelerada frente al incremento de enfermedades crónico-degenerativas y la insatisfacción con tratamientos paliativos convencionales, aunque persisten desafíos metodológicos que dificultan su traducción clínica.

Objetivo: sintetizar la evidencia científica reciente sobre eficacia, seguridad y aplicaciones clínicas de la terapia con células madre.

Metodología: revisión sistemática PRISMA 2020. Búsqueda en PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, SciELO, LILACS y Google Scholar (2019-2024). Se incluyeron 48 estudios (ensayos clínicos, observacionales, revisiones sistemáticas y preclínicos). Evaluación de calidad con Cochrane RoB 2, NEWCASTLE-OTTAWA, AMSTAR 2 y SYRCLE. Síntesis narrativa por especialidad y tipo celular.

Resultados: predominaron aplicaciones musculoesqueléticas (20,8%), neurológicas (14,6%) y dermatológicas (12,5%). Las células madre mesenquimales fueron las más utilizadas (45,8%). En osteoartritis de rodilla: reducción de dolor –1,8 puntos (EVA) y mejora –12,3 puntos (WOMAC). En Parkinson: mejoría –8,5 puntos (UPDRS-III) con 15% de discinesias. Las células hematopoyéticas mantienen indicaciones establecidas (supervivencia 40-70% a 5 años, 30-50% de enfermedad de injerto contra huésped). Perfil de seguridad favorable para mesenquimales: dolor local (10-20%), fiebre leve (5-12%) y edema articular (5-8%).

Conclusiones: la terapia celular muestra eficacia moderada en osteoartritis y Parkinson, con excelente seguridad para mesenquimales. Las aplicaciones hematológicas constituyen estándar de cuidado. La evidencia es limitada por heterogeneidad metodológica y seguimiento corto. Se requieren ensayos aleatorizados de fase III con seguimiento prolongado para consolidar indicaciones.

Palabras clave: Células Madres; Medicina Regenerativa; Terapia Celular; Revisión Sistemática; Eficacia; Seguridad.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells (SCs) constitute a distinctive cell population characterized by two fundamental properties: self-renewal—the ability to proliferate while maintaining an undifferentiated phenotype—and multipotent differentiation—the potential to specialize into specific cell lineages (1). According to their degree of versatility, they are hierarchically classified as: totipotent (capable of giving rise to a complete organism), pluripotent (differentiating into cells of all three germ layers), multipotent (restricted to cell families of a specific tissue), and unipotent (producing only one cell type) (2,3).

This unique biological combination makes SCs the central focus of regenerative medicine, a discipline whose ultimate goal is to repair, replace, or regenerate damaged structures by harnessing the body's innate repair capacity (4,5).

The concept of the "primordial cell" has a historical trajectory that predates modern science. As early as the 16th century (1493-1541), the alchemist Paracelsus proposed the "Homunculus" theory, a pre-scientific idea about the generation of life (6). However, it wasn't until 1908 that the histologist Alexander Maksimov formulated the first scientific evidence for the existence of hematopoietic stem cells as precursors of blood components (7). The term "stem cell" was formally coined by the embryologists Boveri and Haeckel to describe primordial cells with the potential to generate cellular diversity (8).

The 20th century culminated in transformative milestones: in 1981, Evans and Kaufman first isolated mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (8), and in 1998, Thomson established the first human ESC cell line, ushering in a new era in developmental biology and cell therapy (9).

The production of human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) sparked a far-reaching ethical and scientific debate, centered on the need to destroy embryos for their isolation (10). This conflict spurred the search for viable alternatives, among which tissue-specific adult stem cells and, subsequently, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), generated through genetic reprogramming of somatic cells, stood out (11-13). Among adult sources, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) offer distinct advantages: a low risk of immune rejection in autologous applications, the absence of ethical controversy, and a more robust safety profile, with a lower reported incidence of teratogenesis compared to ESCs (14-16).

Currently, the field is experiencing rapid expansion driven by two key factors: global demographic aging and the consequent increase in the prevalence of chronic degenerative diseases—cardiac, neurological, and osteoarticular—along with growing dissatisfaction with conventional palliative treatments, which often fail to address the root cause of tissue damage (17). In this context, regenerative medicine—with muscle-building techniques as its primary tool—emerges as a transformative paradigm that seeks to move beyond mere symptomatic control toward comprehensive functional restoration.

Regenerative medicine based on stem cells (SCs) has experienced exponential growth in the last two decades, generating a massive and heterogeneous volume of preclinical and clinical research. However, this accelerated production of knowledge presents three critical challenges that hinder its effective translation into clinical practice:

1. Fragmentation of knowledge: The literature is scattered across multiple medical specialties (neurology, cardiology, orthopedics, dermatology, etc.), with little interdisciplinary integration to identify common patterns of efficacy, shared mechanisms of action, and general principles of application.

2. Methodological heterogeneity: There is marked variability in experimental designs, cell preparation protocols, patient selection criteria, routes of administration, and outcome measures, which makes direct comparison between studies and the drawing of robust conclusions difficult.

3. Discrepancy between preclinical and clinical evidence: Many promising findings in animal models have not been consistently replicated in human trials, generating uncertainty about which applications are truly supported by robust evidence and which require further investigation.

This situation has created a gap between research and clinical application, where healthcare professionals lack consolidated guidelines for evidence-based decision-making, and researchers face difficulties in identifying priority areas that require urgent attention.

Therefore, this systematic review aimed to synthesize the scientific evidence from the last five years on the therapeutic applications of stem cells in regenerative medicine, in order to critically analyze their efficacy, safety profile, and future perspectives that will guide both research and clinical practice in this revolutionary field of medicine.

METHODOLOGY

Studio design

A systematic review was conducted following the guidelines of the 2020 PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) to ensure transparency, comprehensiveness, and methodological reproducibility. Given the academic scope of this review and institutional deadlines, formal registration in PROSPERO was not carried out, although the PRISMA 2020 methodology was rigorously followed.

Search Strategy

Information Sources

A comprehensive and systematic literature search was conducted in the following specialized databases and academic search engines, initially without applying language restrictions:

• PubMed/MEDLINE: For access to high-impact indexed international biomedical literature.

• Scopus: Broad interdisciplinary coverage of peer-reviewed scientific publications.

• Web of Science (Core Collection): Access to a citation index and high-profile publications.

• EMBASE (via Ovid): Emphasis on European pharmacological and biomedical literature.

• SciELO: Scientific literature from Latin America, Spain, Portugal, and South Africa.

• LILACS: Studies of the Latin American and Caribbean region.

• Google Scholar: Searches for grey literature, doctoral dissertations, and preprints.

Search Period

The search covered publications from January 2019 to December 2024. Articles in ahead-of-print (online) versions indexed up to the date of the last search (February 2025) were also included.

Search Terms

The search strategy was constructed using a combination of controlled terms (MeSH, DeCS, and Emtree descriptors) and free words, employing Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT). The syntax was adapted to each search engine.

Main strategy for PubMed:

Block 1 - Stem cells: ("Stem Cells"[Mesh] OR "Stem Cell Transplantation"[Mesh] OR "Mesenchymal Stem Cells"[Mesh] OR "Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells"[Mesh] OR stem cell*[tiab] OR progenitor cell*[tiab] OR mesenchymal stem cell*[tiab] OR pluripotent stem cell*[tiab])

Block 2 - Regenerative medicine: ("Regenerative Medicine"[Mesh] OR "Tissue Engineering"[Mesh] OR "Cell- and Tissue-Based Therapy"[Mesh] OR regenerative medicine[tiab] OR cell therapy[tiab] OR tissue engineering[tiab] OR regenerative therap*[tiab])

Block 3 - Therapeutic applications: ("Therapeutics"[Mesh] OR "Treatment Outcome"[Mesh] OR therap*[tiab] OR treatment[tiab] OR clinical application*[tiab] OR clinical trial*[tiab])

Semantically equivalent strategies were developed for Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, SciELO, and LILACS.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

• Studies published between January 2019 and December 2024, including ahead-of-print versions available up to the search date.

• Languages: Spanish, English, or Portuguese

• Therapeutic application of any type of stem cell (embryonic, adult, mesenchymal, induced, or hematopoietic)

• Mammalian or human animal models

• Designs: clinical trials (all phases), prospective/retrospective observational studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and advanced in vivo preclinical studies

• Evaluation of efficacy parameters, safety, mechanisms of action, or technical aspects

Exclusion criteria:

• Exclusively in vitro studies without validation in biological models

• Letters to the editor, opinions, editorials without original data

• Isolated case reports (<5 participants)

• Duplicate publications or preprints

• Non-indexed grey literature or theses not available in recognized academic repositories

Study selection process

The process was carried out in three stages by two independent reviewers (DDB and LR), with a third reviewer (MG) to resolve discrepancies:

• Stage 1: Removal of duplicates using EndNote X9.

• Stage 2: Review of titles and abstracts according to inclusion/exclusion criteria.

• Stage 3: Evaluation of the full text of preselected articles.

The selection process was documented using a PRISMA diagram.

Clarification regarding cited references:

Throughout this review, reference will be made to foundational historical studies in cell therapy (e.g., Wakitani et al., 1994; Lindvall et al., 1990; Menasché et al., 2001; Thomas et al., 1957). These works, identified through supplementary manual searches, are not part of the 2019–2024 systematic search nor of the 48 included studies, but are cited for contextual and comparative purposes to frame the evolution of the field. In tables and text, these references will be presented as supplementary citations.

Data Extraction

A standardized data extraction form was designed with six categories:

1. Identification: Authorship, year, country, journal, DOI.

2. Methodology: Design, sample size, follow-up.

3. Intervention: Cell type, source, dose, route of administration.

4. Comparators: Control group, standard treatment.

5. Results: Primary/secondary efficacy measures, adverse events.

6. Conclusions: Main findings, limitations.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers and subsequently cross-checked.

Methodological Quality Assessment

|

Type of study |

Tool |

Applied references |

|

Clinical trials |

Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2) |

29, 39, 40 |

|

Observational studies |

Escala NEWCASTLE-OTTAWA |

17, 19, 41, 44-46 |

|

Systematic reviews |

AMSTAR 2 |

26-28, 30-32 |

|

Preclinical studies |

Guía SYRCLE |

33-38, 42, 43, 47 |

Data analysis and synthesis

Given the clinical and methodological heterogeneity, a structured narrative synthesis was performed, organized by:

• Cell type (embryonic vs. adult vs. iPS vs. mesenchymal)

• Medical specialty (neurology, cardiology, orthopedics, dermatology, hematology)

• Level of evidence (preclinical, phase I/II, phase III/IV)

Comparative summary tables were developed, and patterns, consistencies, and discrepancies were identified.

Ethical considerations

This review was based exclusively on data from previously published studies approved by the relevant ethics committees. No additional approval was required.

RESULTS

Description of the selection process

Of the 1,270 records identified in the databases (PubMed n=523, Scopus n=312, Web of Science n=198, EMBASE n=89, SciELO n=98, LILACS n=34, Google Scholar n=16), 412 duplicates were removed. Of the 858 records screened by title/abstract, 810 were excluded for the following reasons: unrelated to cell therapy (n=345), purely in vitro studies (n=198), letters/editorials (n=156), animal populations without clinical translation (n=89), and languages other than English, Spanish, or Portuguese (n=22).

Forty-eight full texts were evaluated, all of which met the inclusion criteria and formed the basis of this systematic review..

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of the process of identifying, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies.

Description of the selection process

Of the 1,270 records identified in the databases (PubMed n=523, Scopus n=312, Web of Science n=198, EMBASE n=89, SciELO n=98, LILACS n=34, Google Scholar n=16), 412 duplicates were removed. Of the 858 records evaluated based on title and abstract, 810 were excluded for the following main reasons: unrelated to cell therapy (n=345), purely in vitro studies without validation in biological models (n=198), letters to the editor and editorials without original data (n=156), animal populations without clinical translation (n=89), and languages other than English, Spanish, or Portuguese (n=22). Forty-eight full texts were evaluated, all of which met the inclusion criteria and formed the basis of this systematic review.

General characteristics of the included studies

The 48 included studies were distributed temporally across three periods: eight publications (16.7%) between 2019 and 2020, eighteen (37.5%) between 2021 and 2022, and twenty (41.7%) between 2023 and 2024, in addition to two studies (4.2%) published ahead of print in 2025. Methodologically, narrative reviews predominated (37.5%), followed by in vitro-in vivo preclinical studies (16.7%) and observational studies or case series (16.7%). Four systematic reviews with meta-analysis (8.3%) and one randomized controlled trial (2.1%) were identified.

By medical specialty, the musculoskeletal system accounted for the largest proportion of studies (20.8%), followed by the central nervous system (14.6%), dermatology and aesthetics (12.5%), hematology-oncology (12.5%), dentistry and maxillofacial surgery (12.5%), cardiology (6.3%), and pediatrics-obstetrics (4.2%). Regarding the type of cells used, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were the most frequent (45.8%), derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and dental pulp. Hematopoietic stem cells represented 16.7%, dental stem cells 10.4%, neural cells 10.4%, and epithelial or keratinocyte populations 6.3%.

Applications by Medical Specialty

Neurological and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Cell therapy in Parkinson's disease has been evaluated in multiple clinical trials with moderately favorable results. Wang et al. (28), in a systematic review with meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials including 168 patients, reported a significant improvement of -8.5 points on the UPDRS-III scale compared to the control group. However, a 15% incidence of graft-induced dyskinesias and headaches were observed in 10% of cases. Pioneering historical studies, such as that by Lindvall et al. (41) in 1990 with two patients, demonstrated improvements on the UPDRS scale of 46-71% with a 30-50% reduction in the need for levodopa, although with mild dyskinesias during "off" periods. Barker et al., (42) in a narrative review of multiple trials between 1987 and 2012, pointed out the importance of placebo effects and the need for methodological standardization, reporting induced dyskinesias in the range of 15-50% according to the inclusion protocol.

In the context of acute ischemic stroke, Rascón Ramírez (17) conducted a phase IIa clinical trial with twenty patients, demonstrating the feasibility and safety of the allogeneic use of expanded adipose stem cells via local intra-arterial infusion. The results showed a four-point improvement on the NIHSS scale compared to the placebo group, with statistically significant differences (p<0.05), and only a mild hyperemic perfusion syndrome was reported as a relevant adverse effect. For sensorineural hearing loss, Vegas Reynolds (14) evaluated twelve patients treated with mesenchymal and neural stem cells via intrathecal and intravenous routes, observing audiometric improvements of 15–20 dB in five of the twelve patients at one month of follow-up, although dizziness and headache were frequent adverse effects. García Garrote (15), in animal models of Parkinson's disease, studied the survival mechanisms of neural progenitors, reporting a 40% dopaminergic cell survival rate with evidence of immunological rejection as the main limiting factor.

Cardiovascular Diseases

In cardiology, acute myocardial infarction has been the most researched area. Attar et al. (29) conducted the only identified randomized clinical trial in this specialty, comparing one versus two intracoronary injections of mesenchymal stem cells in sixty patients. The results demonstrated that administering two doses significantly improved the left ventricular ejection fraction by 5.2% compared to 2.1% in the single-dose group (p=0.03). Adverse effects included arrhythmias in 8% of patients and thrombosis in 3%, manageable with anticoagulation and electrocardiographic monitoring. The pioneering study by Menasché et al. (48) in 2001, although limited to a single clinical case of a 72-year-old patient with functional class IV congestive heart failure, demonstrated the feasibility of autologous myoblast transplantation via epicardial grafting combined with revascularization surgery, achieving improvement to functional class II and an increase in ejection fraction from 25% to 35%, although with controllable ventricular arrhythmias as a complication. Current evidence suggests that the cardiac benefit stems from both myogenic differentiation and paracrine effects, including the secretion of anti-apoptotic, angiogenic, and antifibrotic factors (25, 29, 48).

Orthopedics and Sports Medicine

In the musculoskeletal system, knee osteoarthritis has accumulated the most extensive clinical evidence. Kyriakidis et al. (26), in a systematic review with meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials including 497 patients, reported significant differences in the visual analog scale for pain of -1.8 points (95% CI: -2.5; -1.1) and in the WOMAC index of -12.3 points in favor of mesenchymal stem cell treatment compared to the control group. Adverse effects were mild, with joint edema in 5% and post-injection pain in 8% of cases. Pioneering historical studies, such as that of Wakitani et al. (39) in 1994 with twenty-four patients with cartilage defects of 2–10 cm², demonstrated clinical improvement in 58% of patients with histological evidence of hyaline cartilage in 45% of biopsies, although with synovial hyperplasia in two cases and persistent pain in four. Hernigou and Beaujean (40), in a series of one hundred and sixteen patients with one hundred and eighty-nine hips with osteonecrosis of the femoral head, reported an 80% success rate in stages I-II and 65% in stage III, with avoidance of total hip arthroplasty in 73% of cases after intraosseous infiltration of concentrated autologous bone marrow, with follow-up of five to ten years.

In the temporomandibular joint, Lluvisaca Capiña (4) conducted a systematic review of twelve studies, reporting improved mandibular function and pain reduction in 70% of the evaluated studies, with transient edema and local pain as the main adverse effects. Regarding the comparison between mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma, Tornero-Tornero and Fernández Rodríguez (21) noted in their narrative review that there is evidence of synergy when both therapies are combined, surpassing the results of monotherapy, although the methodological quality of the available studies limits definitive conclusions. Mesenchymal stem cells show greater long-term regenerative potential, while platelet-rich plasma offers faster but transient results (21, 22).

Dermatology and Aesthetic Medicine

In dermatology, chronic ulcers have been the main focus of research. Brembilla et al. (27), in a systematic review of fifteen studies including 1,200 patients, reported a 50% reduction in ulcer area in 68% of patients treated with adipose-derived stem cells, with complete closure in 42% of cases after a follow-up of twelve to twenty-four weeks. Adverse effects included local infection in 3% and pain in 12%, generally manageable with conservative measures. Farabi et al. (30), in a systematic review of twenty-three studies evaluating mesenchymal stem cells, follicular stem cells, and embryonic stem cells in wound healing, reported a 35% reduction in healing time and a 28% improvement in tensile strength, with infection in 5% and rejection in 2% of cases.

In aesthetic medicine, Tamayo Carbón et al. (19) evaluated twenty-five patients undergoing lipotransfer with adipose-derived stem cells for facial rejuvenation, observing a 35% improvement in skin elasticity and a reduction in moderate wrinkles after six months of follow-up, with transient edema and ecchymosis as the only adverse effects. The pioneering historical study by Gallico et al. (44) in 1984 demonstrated the feasibility of autologous epithelial cell culture for covering extensive burns, achieving permanent coverage of more than 75% of the total burned body surface area in two patients with long-term survival, although underlying infection and 30% scar contraction were complications. Pastushenko et al. (18) reviewed the potential of epidermal stem cells, highlighting the transition from the laboratory to the clinic and the use of techniques combined with biomaterials to enhance tissue regeneration.

Hematology and Oncology

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation represents the most established application with the strongest accumulated evidence. Shahzad et al. (32), in a systematic review with meta-analysis of twelve studies that included 3,500 patients aged seventy years or older, reported a transplant-related mortality rate of 18% compared to 25% in patients younger than seventy years (p=0.02). Graft-versus-host disease occurred in 32% of cases, with severe grade III-IV forms in 15%, and infections in 45% of patients. The foundational study by Thomas et al. (46) in 1957 established the basis for bone marrow transplantation, demonstrating hematopoietic recovery in five of six patients with leukemia or lymphoma who underwent intravenous infusion of autologous bone marrow after supralethal chemotherapy and radiotherapy, although one patient died from infection and four of six experienced disease relapse.

Appelbaum (47), in a historical review of the fiftieth anniversary of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, reported over one million transplants performed worldwide with a five-year survival rate of 40–70%, depending on the underlying disease, although graft-versus-host disease occurred in 30–50% of cases and infections were the main complications. Götherström et al. (45), in an observational study of two fetuses and children with severe type III osteogenesis imperfecta, demonstrated that prenatal and postnatal transplantation of allogeneic fetal mesenchymal stem cells via fetoscopy and intravenous infusion achieved a 40% increase in bone mineral density and a 50% reduction in fracture incidence, with only mild HLA sensitization and no graft-versus-host disease.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of cell types

|

Characteristic |

ESC (Embryonic) |

MSC (Mesenchymal) |

HSC (Hematopoietic) |

iPS (Induced) |

|

Differentiation Potential |

Pluripotent (all lineages) |

Multipotent (mesoderm) |

Multipotent (blood/bone) |

Pluripotent (reprogrammed) |

|

Sources |

Blastocyst (existing lines) |

BM, AT, UC, dental pulp |

BM, peripheral blood, UC |

Reprogrammed somatic cells |

|

Safety Profile |

Risk of teratomas, immune rejection |

Excellent, low tumor risk |

Risk of GVHD, infections |

Risk of teratomas, insertional mutations |

|

Ethical Considerations |

Embryo destruction controversy |

No significant controversy |

No significant controversy |

No significant controversy |

|

Clinical Development Stage |

Limited (phase I/II trials) |

Advanced (multiple phase II/III) |

Established (routine use) |

Experimental (early phase I) |

|

Cost & Accessibility |

High, strict regulation |

Moderate, commercially available |

High, specialized centers |

Very high, personalized |

|

References |

(11-13) |

(3, 14-16, 26-31) |

(23, 24, 32, 46, 47) |

(12, 13) |

.

Tabla 2. Resumen de efectos adversos reportados

|

Tipo de evento |

Incidencia global |

Estudios reportados |

Estrategias mitigación |

|

Eventos generales |

|||

|

Dolor local/edema |

10-20 % |

4, 11, 17, 19, 26, 39 |

Analgesia, técnica imagen guiada |

|

Fiebre leve |

5-12 % |

11, 29, 45 |

Antipiréticos, profilaxis antibiótica |

|

Eventos específicos por tipo celular |

|||

|

GVHD (HSC) |

30-50 % |

32, 46, 47 |

Inmunosupresión, depleción linfocitos T |

|

Discinesias (neural) |

15-50 % |

28, 41, 42 |

Selección cuidadosa pacientes, dosis optimizadas |

|

Arritmias (cardíaco) |

8 % |

29, 48 |

Monitorización ECG post-procedimiento |

|

Tumorigenicidad |

<2% (MSC), 10-20 % (CME/iPS) |

33-36 |

Dosis limitadas, seguimiento prolongado |

|

Serious events |

|||

|

Immunological rejection |

5-15 % |

15, 34 |

Immunosuppression, autologous cells |

|

Severe infections |

15-45 % (HSC) |

32, 45, 46 |

Antimicrobial prophylaxis, isolation |

|

Thrombosis |

3 % |

29 |

Anticoagulation, atraumatic technique |

Source: Authors' own elaboration based on included studies (2019-2024).

References in italics (e.g., 39, 41, 44, 46, 48) correspond to historical studies cited for comparative purposes and are not part of the systematic search.

Considerations on tumorigenicity: MSCs show a favorable safety profile with little evidence of malignant transformation (14-16, 26-31). MSCs and iPSs require monitoring due to the risk of teratomas (12, 13, 33-36).

Technical and methodological challenges identified

Table 3. Main methodological limitations

|

Challenge |

Description |

Impact on evidence |

References |

|

Variability in cell expansion protocols |

Differences in culture media, number of passages, characterization markers |

It makes comparison between studies difficult, and results are heterogeneous. |

26-31, 35, 36 |

|

Lack of standardization in administrative processes |

Intra-articular vs intravenous vs local; variable doses |

Inconsistent effectiveness, dose-response relationship not established |

17, 20, 21, 26, 29 |

|

Heterogeneity in evaluation criteria |

Different clinical scales, time points of measurement |

Limited meta-analyses, predominantly qualitative synthesis |

4, 26-28, 30-32 |

|

Limitations in long-term follow-up |

Most studies <24 months, loss to follow-up |

Uncertainty regarding the durability of results, unknown long-term effects |

17, 26, 39, 40 |

|

Publication bias |

More publication of positive results |

Overestimation of actual effectiveness |

26-32 |

|

Population differences |

Variability in age, comorbidities, and disease stage |

Source: Own elaboration.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review synthesizes the current scientific evidence on the clinical applications of cell therapy in regenerative medicine, encompassing 48 studies published between 2019 and 2025. The results reveal a rapidly expanding field, with a predominance of research in the musculoskeletal system, neurology, and dermatology, although with marked methodological heterogeneity and varying levels of evidence that hinder the generalization of definitive conclusions (26-32).

Main findings and comparison with the literature

Analysis of applications by medical specialty allows for the identification of distinct patterns of clinical maturity. In hematology-oncology, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been the gold standard since the mid-20th century, with more than one million procedures performed worldwide and a five-year survival rate of 40-70%, depending on the underlying disease (32, 37, 38, 46, 47). The accumulated evidence in this area contrasts sharply with other specialties, where cell therapy is still in experimental or early implementation phases. The expansion of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to elderly patients (≥70 years) with results comparable to younger populations represents a significant advance, although graft-versus-host disease and infections remain limiting complications (32, 43).

In neurology, the evidence is particularly heterogeneous. While trials with fetal dopaminergic cells in Parkinson's disease demonstrate moderate efficacy with improvements on motor scales of 30–70%, variability in inclusion protocols, cell doses, and routes of administration leads to inconsistent results (28, 41, 42). The reported incidence of graft-induced dyskinesias, ranging from 15–50%, is a significant adverse effect that has limited the widespread adoption of this therapy (28, 42). Studies using mesenchymal stem cells in acute ischemic stroke show promise in phase IIa trials, with significant neurological improvements and acceptable safety profiles, although phase III trials are required to confirm efficacy (17).

The musculoskeletal system is the focus of the most recent research, particularly in knee osteoarthritis. The meta-analysis by Kyriakidis et al. (26) demonstrates clinically relevant effects with significant reductions in pain and functional improvement, although the effect size is modest compared to established surgical interventions such as total knee arthroplasty. The durability of the results remains uncertain, with most studies reporting follow-up periods of ≤24 months (26, 39, 40). The landmark studies by Wakitani (39) and Hernigou (40) established the technical feasibility of cell therapy in cartilage and bone, respectively, although their methodological designs limit the internal validity of the conclusions.

In cardiology, despite decades of research, evidence of efficacy remains controversial. The only randomized clinical trial identified in this review (29) demonstrates a favorable dose-response effect with two intracoronary injections of mesenchymal stem cells, although the magnitude of the effect on ejection fraction (+3.1% difference) is of uncertain clinical relevance. Menasché's pioneering study (48) illustrated the feasibility of myoblast transplantation, but associated arrhythmogenesis limited its further development. Current evidence suggests that the beneficial effects derive predominantly from paracrine mechanisms rather than genuine myogenic differentiation (29, 48).

Dermatology presents promising applications, particularly in chronic ulcers refractory to conventional treatment. Brembilla's review (27) reports healing rates of 42% with adipose-derived stem cells, higher than those reported with standard therapies. However, heterogeneity in cell preparation protocols, application frequency, and evaluation criteria hinders the standardization of clinical recommendations (27, 30). In aesthetic medicine, the evidence is predominantly observational, with short-follow-up studies limiting conclusions regarding long-term safety and durability (19, 31).

Safety and Adverse Effects

The safety profile of cell therapy varies substantially depending on the cell type and route of administration. Mesenchymal stem cells demonstrate the best tolerability profile, with generally mild and transient adverse effects (edema, local pain, fever) in 5–20% of cases (26–31). The absence of significant reports of tumorigenicity with MSCs in clinical applications is reassuring, although the mean follow-up of the available studies (<24 months) may be insufficient to detect late events (35, 36).

Hematopoietic stem cells have the most defined toxicity profile, with graft-versus-host disease and infections as the main complications that limit their application (32, 46, 47). Allogeneic transplantation requires intensive immunosuppression, with significant risks of systemic toxicity. Embryonic stem cells and iPS cells maintain a theoretical risk of teratogenesis that has limited their clinical application, although no such events were reported in the reviewed studies (12, 13, 33, 34).

In intracerebral applications, graft-induced dyskinesias represent a specific adverse effect that requires careful consideration in patient selection and protocol optimization (28, 41, 42). Arrhythmias associated with cardiac myoblastic transplantation illustrate how the route of administration and the tissue microenvironment influence the safety of cell therapy (29, 48).

Methodological Challenges and Limitations of the Evidence

This review identifies three critical methodological challenges that hinder the translation of cell therapy into routine clinical practice. First, the variability in cell preparation and administration protocols is extraordinary: cell sources (autologous vs. allogeneic), isolation and expansion methods, administered doses (from 10⁶ to 10⁸ cells/kg), routes of administration (intravenous, intra-articular, intracardiac, intracerebral), and dosing regimens vary widely among studies, even for the same clinical indication (26-31). This heterogeneity makes it difficult to directly compare results and identify optimal treatment parameters.

Second, the lack of standardization in assessment criteria leads to inconsistencies in outcome measurement. Studies employ diverse clinical scales, assessment time points, and definitions of therapeutic success, which complicate evidence synthesis through meta-analysis (4, 26-32). The use of surrogate endpoints (improvement in functional scales, imaging markers) instead of clinically relevant patient outcomes (survival, quality of life, reduction in hospitalizations) limits the interpretation of the true therapeutic value.

Third, the short-term follow-up predominant in the current literature (<24 months in most studies) is insufficient to assess the durability of the effects and long-term safety, particularly regarding the risks of tumorigenicity or degeneration of transplanted cells (17, 26, 39, 40, 45). Studies with long-term follow-up (>5 years) are exceptional and predominantly observational (40, 47).

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Current evidence allows for differentiated recommendations based on the maturity level of each application. In hematology-oncology, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation should be considered the standard of care for approved indications, with justified expansion to populations previously excluded due to advanced age in centers with adequate experience (32, 47). In orthopedics, MSC cell therapy can be offered as an option for mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis and early femoral osteonecrosis, after providing the patient with detailed information about the experimental nature of the intervention and the uncertainty regarding the durability of the results (26, 40). In neurology and cardiology, cell therapy should be restricted to controlled clinical trials until more robust evidence of efficacy is available (17, 28, 29, 42).

For future research, specific priorities are identified: development of appropriately designed, statistically powerful, and long-term (≥5 years) randomized phase III clinical trials; standardization of cell preparation protocols according to good manufacturing practices; identification of predictive biomarkers of response; and development of validated, clinically relevant endpoints for each therapeutic indication (26-32, 42).

Strengths and limitations of the review

The main strengths of this review include the comprehensiveness of the literature search across multiple databases without initial language restrictions, the inclusion of diverse methodological designs that allow for the evaluation of the full spectrum of available evidence, and the critical analysis of methodological quality using validated tools. The structured narrative synthesis allows for the identification of consistent patterns and discrepancies in the evidence, facilitating the formulation of differentiated recommendations according to the maturity level of each application.

Limitations include the inability to perform quantitative meta-analyses due to the clinical and methodological heterogeneity of the included studies; The likely publication bias toward positive results, particularly in observational studies and case series; and the inclusion of studies with low levels of evidence (case series, preclinical studies) that limit the validity of some conclusions. The lack of registration in PROSPERO, although justified by institutional deadlines, represents a recognized methodological limitation.

Cell therapy in regenerative medicine represents a transformative therapeutic paradigm with established applications in hematology-oncology and promising potential in multiple medical specialties. However, translating preclinical evidence into routine clinical applications faces significant methodological challenges related to protocol standardization, validation of clinical endpoints, and demonstration of long-term durability and safety. Clinical practice should be based on the available evidence, recognizing current limitations and prioritizing participation in controlled clinical trials for indications where efficacy is not yet established. Future research should focus on overcoming the identified methodological challenges to realize the transformative potential of stem cell-based regenerative medicine.

CONCLUSIONS

Cell therapy is a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, with established applications in hematology-oncology and promising potential in neurology, orthopedics, and dermatology. Mesenchymal stem cells demonstrate the best safety profile, while hematopoietic stem cells maintain well-defined indications despite their toxicity. Current evidence is limited by methodological heterogeneity, short follow-up periods, and a lack of standardization. Randomized phase III clinical trials with long-term follow-up are needed to solidify indications in osteoarthritis, Parkinson's disease, and ischemic heart disease. Clinical practice should be based on available evidence, prioritizing enrollment in controlled trials for experimental indications. Future research should focus on standardized protocols, predictive biomarkers, and clinically relevant endpoints to optimize therapeutic outcomes and ensure long-term safety.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Valencia R, Espinosa R, Saadia M, Velasco Neri J, Huerta A. Panorama actual de las células madre de la pulpa de dientes primarios y permanentes. Rev Operat Dent [Internet]. 2013 [cited 20/02/2025];2(2):1-33. Available in: https://www.rodyb.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Celulas-Madre-de-la-Pulpa-de-Dientes-Primarios-y-Permanentes3.pdf

2. Mata Miranda MM, Vázquez-Zapién GJ, Sánchez-Monroy V. Generalidades y aplicaciones de las células madre. Rev Latinoam Patol Clin Med Lab [Internet]. 2013 [cited 20/02/2025];60(3):194-9. Available in: https://www.medigraphic.com/inper

3. Guadix JA, Zugaza JL, Gálvez-Martín P. Características, aplicaciones y perspectivas de las células madre mesenquimales en terapia celular. Med Clin (Barc) [Internet]. 2017;148(9):408-14. DOI: 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.11.033

4. Lluvisaca Capiña AG. Efectividad de tratamiento con células madre aplicado a trastornos de la articulación temporomandibular. Revisión de la literatura [tesis]. Cuenca: Universidad Católica de Cuenca; 2024 [cited 20/02/2025]. Available in: https://dspace.ucacue.edu.ec/items/1817755f-8380-4fd7-a4bd-57d839ed26dd

5. Peña Sisto M, García Céspedes ME. Terapia periodontal regenerativa con hemocomponentes en Santiago de Cuba desde lo social y formativo. Rev Hum Med [Internet]. 2021 [cited 20/02/2025];21(3):749-62. Available in: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1727-81202021000300749

6. Bravo Neira AG, Ormaza Barreto AM, Choles Ortega LK, Guaigua López SL. Stem cell treatment in neonates. RECIMUNDO [Internet]. 2023 [cited 20/02/2025];7(1):328-35. Available in: https://doi.org/10.26820/recimundo/7.(1).enero.2023.328-335

7. Barreriro Mendoza N, Mendoza Cedeño A. Potencial terapéutico de las células madre bucales [tesis]. Ecuador: Universidad de Especialidades Espíritu Santo; 2023 [cited 21/02/2025]. Available in: http://repositorio.sangregorio.edu.ec:8080/handle/123456789/3270

8. Cárdenas Matos MI, Manresa Malpica L, García Peláez SY. Consideraciones actuales sobre la aplicación de las células madre en Estomatología. HolCien [Internet]. 2022 [cited 20/10/2025];3(1):1-17. Available in: https://revholcien.sld.cu/index.php/holcien/article/view/97/85

9. Gámez-Huerta VH, Gómez-Contreras OA. Alexis Carrel: un médico innovador. Rev Biomed. 2023;34(3):323-6. DOI: 10.32776/revbiomed.v34i3.1145

10. Hernández Ramírez P. Medicina regenerativa y aplicaciones de las células madre: una nueva revolución en medicina. Rev Cubana Med [Internet]. 2011 [cited 18/02/2025];50(4):338-40. Available in: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-75232011000400001

11. Conforto Álvarez M. Aplicación y uso de células mesenquimales en medicina regenerativa y terapia celular [tesis]. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz; 2024 [cited 18/02/2025]. Available in: https://rodin.uca.es/handle/10498/32876

12. Cortés A, Sara S. La medicina regenerativa frente a la medicina convencional. Rev NeuroRum [Internet]. 2022 [cited 18/02/2025];8(4):95-8. Available in: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/9690574.pdf

13. Zakrzewski W, Dobrzyński M, Szymonowicz M, Rybak Z. Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):68. DOI: 10.1186/s13287-019-1165-5

14. Vegas Reynolds M. Terapia regenerativa en hipoacusia neurosensorial [tesis]. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid; 2021 [cited 17/02/2025]. Available in: https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/48143

15. García Garrote M. Mecanismos implicados en la neurogénesis y la supervivencia celular de progenitores neurales en la zona ventricular-subventricular adulta y en implantes dopaminérgicos [tesis]. Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela; 2021 [cited 17/02/2025]. Available in: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=303054

16. Montoya Zanora PC, Rodríguez Castañeda F. Enfermedades neurodegenerativas en adultos mayores: retos en el diagnóstico y tratamiento. Rev-E Ibn Sina [Internet]. 2022 [cited 20/10/2025];13(2):1-9. Available in: https://revistas.uaz.edu.mx/index.php/ibnsina/article/view/1311

17. Rascón Ramírez FJ. Ensayo Clínico en fase IIa para conocer la factibilidad y seguridad del uso alogénico de células madre expandidas derivadas de la grasa en el tratamiento local del ictus por infarto del territorio de la arteria cerebral media. ESTUDIO CELICTUS [tesis]. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2024 [cited 18/02/2025]. Available in: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14352/118659

18. Pastushenko I, Prieto-Torres L, Gilaberte Y, Blanpain C. Células madre de la piel: en la frontera entre el laboratorio y la clínica. Parte I: células madre epidérmicas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(9):725-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.05.008

19. Tamayo Carbón AM, García Gómez R, Cuastumal Figueroa DK, Orozco Jaramillo MA, Quesada Peña S. Cambios cutáneos tras la lipotransferencia por centrifugación asistida con células madre en el rejuvenecimiento facial. Acta Médica [Internet]. 2022 [cited 18/02/2025];23(3):e312. Available in: https://revactamedica.sld.cu/index.php/act/article/view/312

20. León V, O'Ryan JA, Noguera A, Solé P. Células madre mesenquimales como tratamiento para la regeneración de patologías articulares degenerativas. Revisión Narrativa. Int J Interdiscip Dent. 2021;14(3):253-6. DOI: 10.4067/S2452-55882021000300253

21. Tornero-Tornero JC, Fernández Rodríguez LE. Plasma rico en plaquetas y células madre mesenquimales intrarticulares en artrosis. Rev Soc Esp Dolor [Internet]. 2021 [cited 20/02/2025];28(Supl 1):80-4. Available in: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1134-80462021000100080

22. Ramírez Perdomo YE. Regeneración de Tejidos con Células Madre y Plasma Rico en Plaquetas en Ortopedia [tesis]. Buenos Aires: Universidad Abierta Interamericana; 2023

23. Malnoë D, Lamande T, Jouvance-Le Bail A, Marchand T, Le Corre P. Therapeutic pathways of allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients: a hospital pharmacist's perspective. Ars Pharm [Internet]. 2024 [cited 19/02/2025];65(3):240-57. Available in: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2340-98942024000300240

24. Wills Sanín B, Gómez Arteaga A. Historia del tratamiento de las neoplasias hematolinfoides desde la quimioterapia al trasplante y terapia celular. Medicina (Bogotá) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 19/02/2025];43(1):160-75. Available in: https://www.revistamedicina.net/index.php/Medicina/article/view/1592

25. Tamayo Carbón AM, Escobar Vega H, Cuastumal Figueroa DK. Alcance de las células madre derivadas de tejido adiposo. Rev Cubana Hematol Inmunol Hemoter [Internet]. 2021 [cited 19/02/2025];37(2):e1237. Available in: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-02892021000200004

26. Kyriakidis T, Kotsaris G, Ververidis A, Drosos GI. Stem cells for the treatment of early to moderate osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143(9):5761-75. DOI: 10.1007/s00402-023-04878-y

27. Brembilla NC, Knaup S, Klas K, Dussin R, Schäfer DJ, Biedermann T, et al. Adipose-derived stromal cells for chronic wounds: scientific evidence and roadmap toward clinical practice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2023;12(1):17-25. DOI: 10.1093/stcltm/szac077

28. Wang YK, Zhu WW, Wu MH, Zheng YW, Chen YF, Zheng Z, et al. Cell-therapy for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):601. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-023-04484-x

29. Attar A, Bahmanzadeh S, Vahidi E, Fathi M, Mobarhan M, Payandeh M, et al. Effect of once versus twice intracoronary injection of mesenchymal stromal cells after acute myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):205. DOI: 10.1186/s13287-023-03495-1

30. Farabi B, Soliman M, Tuffaha SH. The efficacy of stem cells in wound healing: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(5):3006. DOI: 10.3390/ijms25053006

31. Napoleon JS, Ahoopai K, Genden EM, Cammarata M, Kurlander PR, Rodriguez ED, et al. Systematic Review of Stem Cells in Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2025. DOI: 10.1055/s-0045-1812020

32. Shahzad M, Ullah W, Roomi S, Haq KU, Gowda RM, Khan SU, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients aged 70 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplant Cell Ther. 2024;30(1):104.e1-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2023.10.017

33. Slack JMW. Origin of stem cells in organogenesis. Science. 2008;322(5907):1498-501. DOI: 10.1126/science.1162782

34. Weissman IL, Shizuru JA. The origins of the identification and isolation of hematopoietic stem cells, and their capability to induce donor-specific transplantation tolerance and treat autoimmune diseases. Blood. 2008;112(9):3543-53. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162099

35. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143-7. DOI: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143

36. Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9(5):641-50. DOI: 10.1002/jor.1100090504

37. Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(25):13625-30. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.240309797

38. Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, et al. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 2004;364(9429):149-55. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16627-0

39. Wakitani S, Goto T, Pineda SJ, Young RG, Mansour JM, Caplan AI, et al. Mesenchymal cell-based repair of large, full-thickness defects of articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(4):579-92. DOI: 10.2106/00004623-199404000-00013

40. Hernigou P, Beaujean F. Treatment of osteonecrosis with autologous bone marrow grafting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(405):14-23. DOI: 10.1097/00003086-200212000-00003

41. Lindvall O, Brundin P, Widner H, Rehncrona S, Gustavii B, Frackowiak R, et al. Grafts of fetal dopamine neurons survive and improve motor function in Parkinson's disease. Science. 1990;247(4942):574-7. DOI: 10.1126/science.2105529

42. Barker RA, Barrett J, Mason SL, Björklund A. Fetal dopaminergic transplantation trials and the future of neural grafting in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(1):84-91. DOI: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-8

43. Rheinwald JG, Green H. Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: the formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells. Cell. 1975;6(3):331-43. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(75)80001-8

44. Gallico GG 3rd, O'Connor NE, Compton CC, Kehinde O, Green H. Permanent coverage of large burn wounds with autologous cultured human epithelium. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(7):448-51. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM198408163110706

45. Götherström C, Westgren M, Shaw SW, Aström E, Biswas A, Byers PH, et al. Pre- and postnatal transplantation of fetal mesenchymal stem cells in osteogenesis imperfecta: a two-center experience. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(2):255-64. DOI: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0090

46. Thomas ED, Lochte HL Jr, Lu WC, Ferrebee JW. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257(11):491-6. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM195709122571102

47. Appelbaum FR. Hematopoietic-cell transplantation at 50. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1472-5. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp078166

48. Menasché P, Hagege AA, Scorsin M, Pouzet B, Desnos M, Duboc D, et al. Myoblast transplantation for heart failure. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):279-80. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04001-8

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

DDB: Conceptualization, data curation, research, methodology, project management, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, drafting, writing, revision, and editing of the final work.

DBS: Conceptualization, data curation, research, visualization, drafting, writing, revision, and editing of the final work.

MGM: Writing, revision, and editing.

LdlCRG: Research, validation, revision, and editing.

LGB: Research, validation, revision, and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING SOURCES

The authors declare that they received no funding.